Author's late discovery of Native heritage was a 'cosmic blessing'

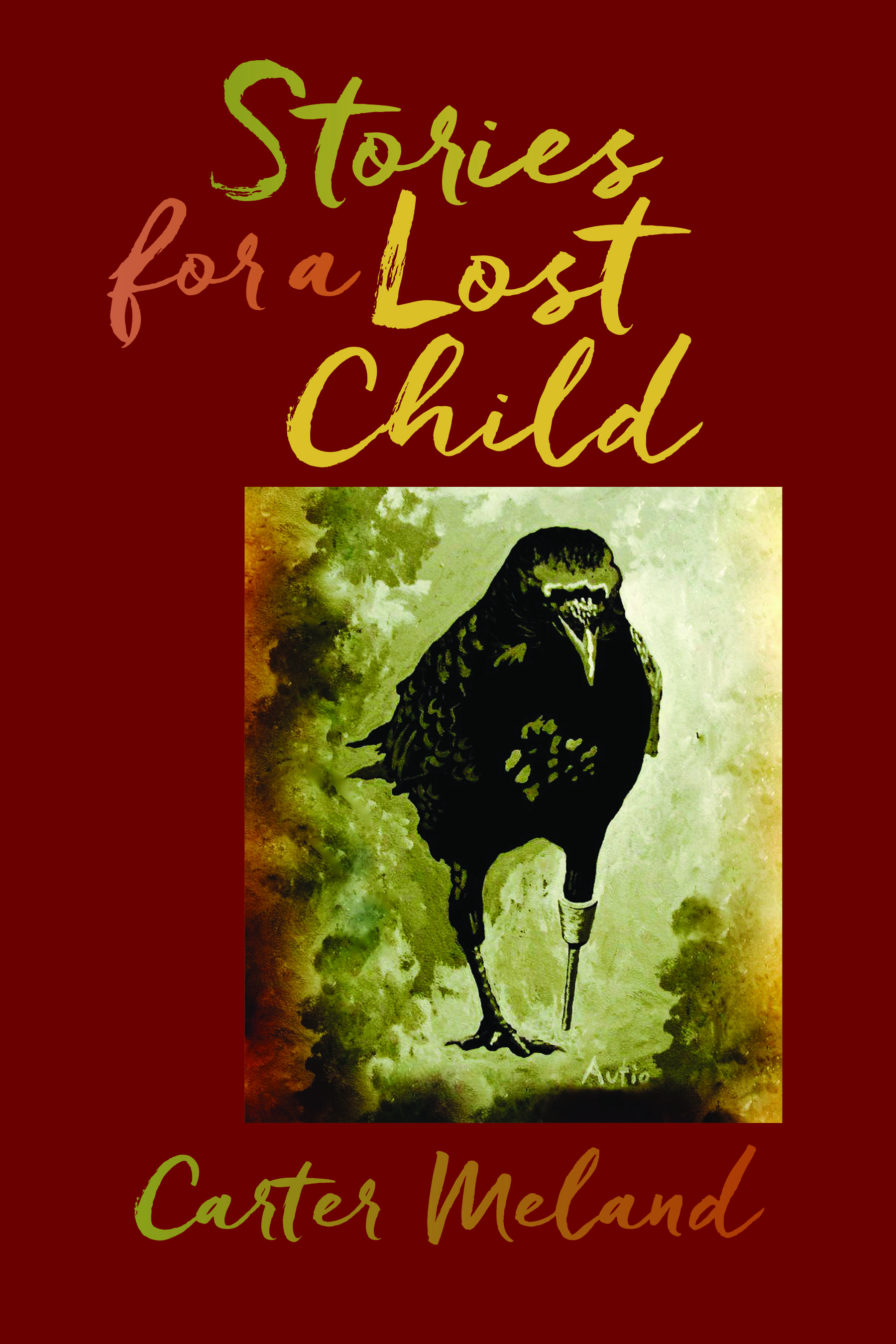

Meland's book "Stories for a Lost Child" is a finalist in the best novel category at this weekend's Minnesota Book Awards. It's fiction, but reflects Meland's own experience.

Growing up, he said, there were gaps in his family history.

"My dad never knew his biological father," he said. "And we never knew much about him. My grandmother was reluctant to talk about him, and we tried to respect that."But that changed one day about 25 years ago, when Meland was "getting close to 30," he said.

Meland recounted some Minnesota history: Back in 1985, Congress passed the White Earth Land Settlement act. It was designed to resolve longstanding disputes over land ownership on the northern Minnesota reservation.

Originally tribal members were allotted land on the reservation, but thousands of acres were illegally sold to nonmembers in the early 20th century. Under the act, the search began for heirs of people originally allotted land to give them compensation.

"And my dad was one of their heirs, through his father. So he gets a phone call one day," Meland said. The family had no idea of its Anishinaabe heritage.

But, as Meland tells it: "In my world of cosmic coincidences, or perhaps cosmic blessings, I was already in grad school beginning to study Native literature. So I kind of feel like somebody was telling me stuff."

Meland's studies took on new significance. He learned a little of the Ojibwe language. He also began writing short stories. Some were based on traditional characters, and others just sprang into his mind.

"Stories about Indians in space, and Bigfoot, Mesabe or Sasquatch or whatever you want to call him. We say Mesabe in Anishinaabemowin," said Meland, using the Ojibwe word for the language. "And other stories, including one about a 17th century missionary to the Anishinaabe."

Eventually he connected the tales, and they became the novel "Stories for a Lost Child." It's about a teenage girl called Fiona who receives a mysterious box filled with writing. It's from her grandfather, a man who abandoned her mother years ago.

"But wanting some kind of contact, and sending this box of stories to Fiona, perhaps 18 years after he died, through an intermediary," he said.

It's a surreal collection, linked by letters from her grandfather, which are also in the box. In one he admits he's a con man and an unreliable guide. However, in time — and through a few misadventures of her own — Fiona begins to understand her heritage.

"And what I realized, as I was reading the book and talking to people about the book, is what motivates my writing was what does it mean not to know you have Anishinaabe heritage, right?" said Meland.

When he taught Native literature he discovered that his experience of learning late about his heritage was not unusual.

"I have had many moving conversations with students who know they have Anishinaabe heritage, or Dakota heritage or Cree heritage, or what have you, but they don't know what it means," he said.

And he's likely to have more of those conversations now that he's up for a Minnesota Book Award on Saturday evening. The other nominees in the best novel/short story category are Louise Erdrich for "Future Home of a Living God," A. Rafael Johnson for "The Through," and Lesley Nneka Arimah for "What it Means when a Man falls from the Sky."

Meland says it's significant that none of the nominees comes from what he calls the majority culture.

"The literary community is very hungry for stories from under-represented voices, or slightly less misrepresented voices, and it's really exciting," he said.

When you read a really good book, Meland said, you become the protagonist in that book. When you are of a background different from that of the protagonist, that can be a good thing, he said.

He will read from his novel at Subtext Books in St. Paul at 7 p.m. May 9 and at the Brown Bag Lunch with Author series at the Brainerd Public Library on June 18.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please: Share your reaction, your thoughts, and your opinions. Be passionate, be unapologetic. Offensive remarks will not be published. We are getting more and more spam. Comments will be monitored.

Use the comment form at the bottom of this website which is private and sent direct to Trace.