By Trace Hentz

I woke up with two thoughts: there are two victims of adoption who need help and not necessarily from each other: the adoptee and the first mother. Each has its own burden and neither can heal the other.

I woke up with two thoughts: there are two victims of adoption who need help and not necessarily from each other: the adoptee and the first mother. Each has its own burden and neither can heal the other.

“I get up. I walk. I fall down. Meanwhile I keep dancing.” That is a line in the book “Bird by Bird” by Ann Lamott. Her comical book offers instructions on writing and life and so far -- I’ve had good belly laughs. Yep, Ann made a funny book!

In

part two, Ann was fighting herself over jealousy of another writer

friend. She wrote, “Sometimes this human stuff is slimy and pathetic -

jealousy especially so - but better to feel it and talk about it and

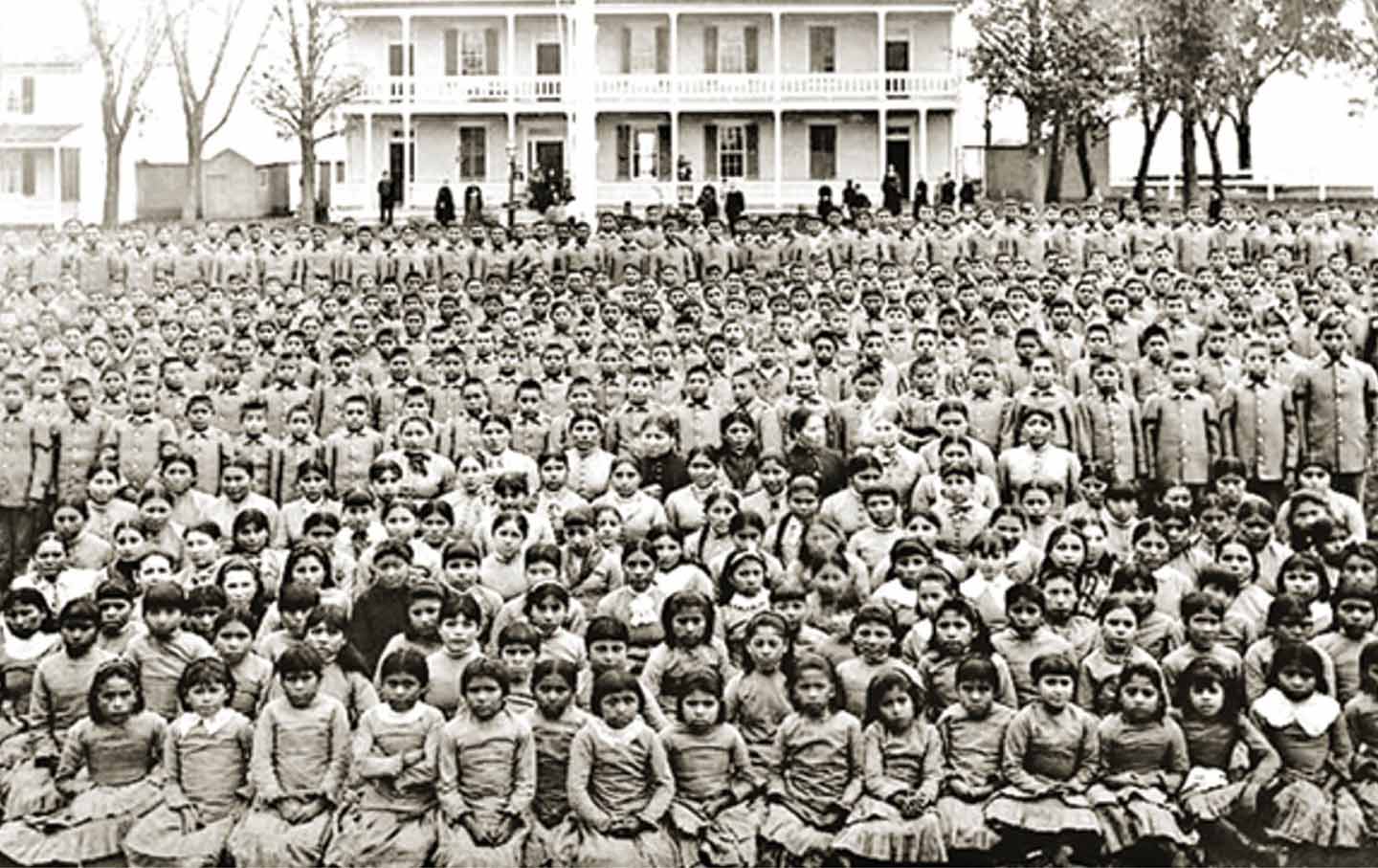

walk through it than to spend a lifetime poisoned by it."Poison is nothing to mess with. I spoke with an adoptee friend last night and Levi is sure we adoptees need to create new ceremonies, even some just for us adoptees. I was nodding at every word Levi said. A lifetime of isolation from what we know to be ours, our blood rights as Indigenous People, our language and culture and the healing offered by participating in ceremony, it was not ours growing up white and adopted and assimilated.

But we adoptees are not victims, Levi said. No, we are changed by adoption but not its victims.

I

thought about ceremony, what ceremony I missed growing up, and what

other Indian people probably took for granted growing up. That does make

me jealous. I didn’t get to meet my grandmothers in flesh, only in

dreams.

I

am sad I do not how to make my own regalia. I see others dance at

powwow and wish someone had time to teach me what I need to know.

I can think of a million things I’d like to know. When I met relatives in Illinois last year, I was over the moon happy. My Harlow cousins filled many holes in my heart.

I am in reunion. Jealousy is not my poison.

For those not in reunion, their hearts ache. We need to find a way to heal them.

Levi Eagle Feather has contributed to this blog.

This is the lost post, Part 4 of the series.