Subscribe to Fiat Vox.

See all podcast episodes.

This is the second part of the two-part series about how

disability has been and continues to be used as a way to control and

profit from Native populations.

Last week, we heard from UC Berkeley’s Ella Callow about how the U.S. government built a psychiatric institution in the early 1900s to imprison Native Americans.

Today, Callow discusses how Native communities are still

forced to exist in societal systems that use disability to justify

taking Native children away from their families, and to ultimately

control, and make money from, their lives.

A

Butte County courthouse in Belle Fourche, South Dakota. In South

Dakota, a Native child is 11 times more likely to be placed in the

foster care system than a white child. (Photo by J. Stephen Conn via Flickr)

Read a transcript of Fiat Vox episode #67: “How state courts use disability to remove Native children from their homes”:

This is Fiat Vox, a Berkeley News podcast. I’m Anne Brice.

Last week, we spoke to UC Berkeley’s Ella Callow about how,

nearly 100 years ago, the U.S. government built a psychiatric

institution in South Dakota to forcibly commit and imprison Native

Americans, often for reasons that had nothing to do with having a mental

illness.

If you haven’t listened to it yet, I recommend going back and listening to it just to get a little bit more context.

Today, in the second part of the two-part series, Callow, the

director of the Office of Disability Access and Compliance at Berkeley

and who spent more than a decade as a lawyer before coming to Berkeley

fighting for the rights of parents with disabilities, says that Native

communities are still forced to exist in societal systems that use

disability to justify taking Native children away from their families,

and to ultimately control, and make money from, their lives.

Ella

Callow, director of the Office of Disability Access and Compliance at

UC Berkeley, is writing an article about how disability has been and

continues to be used as a way to profit from and control Native

populations. (Photo courtesy of Ella Callow)

Ella Callow: One of the things that really concerns

me is the fact that this has bled into child welfare issues. Native and

disabled people have very disparate impacts of child welfare involvement

and removal of their children. In the American Indian context, the

Indian Child Welfare Act should be a protection against this.

The Indian Child Welfare Act was passed by Congress in 1978,

establishing minimum federal standards for when and how state agencies

could remove Native American children from their parents’ custody and

their cultural environment.

But when a parent’s disability is involved, says Callow, it’s used to override their cultural identity.

Ella Callow: What we see is that, often, if the

parent has a disability, there’s an effort by the state in state courts,

which unfortunately is where the cases often take place — they should

be taking place in tribal court, but often they take place in state

court, to say, ‘Well, we know that we should have, perhaps, a cultural

expert. We know that we are supposed to place a child with kin and do

all these things. But we all know that the real issue here is that Mom

is schizophrenic, or that Dad is blind. And so, this really isn’t about

all that Indian stuff. This is about the disability.’

[Music: “Morning Glare” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Although the U.S. Department of Justice issued guidelines in

2015 that specifically stated that the Americans with Disabilities Act

applies to all child welfare cases, it rarely ends up protecting Native

families in court, says Callow.

Instead, counsel on both sides often kind of give up,

affirming the underlying societal belief that parents with disabilities

aren’t capable of raising their own children.

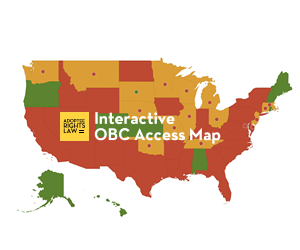

In South Dakota, for example, a Native American child is 11

times more likely to be placed in the foster care system than a white

child. And even when there are many Native foster homes available, a

majority of those Native children are placed with non-Native families or

in group centers instead.

Ella Callow: In the cases in South Dakota just a few

years ago, the state got into a great deal of trouble for its court’s

practices around child welfare in the Native community. And what was

really interesting was that things came to light, like the fact that

they designate every single Native child they remove and place into

foster care as disabled. And when they do that, they get more money.

So, what we’re seeing again is they’re taking these children out of

the community, they’re identifying them as disabled and making money,

and they’re controlling them in state settings or non-Native settings in

a way that’s detrimental to the children, and is profitable to the

state.

[Music: “Silent Flock” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Ella Callow: What I found in my research is that

when tribes take control of their own child welfare systems, which many

have done in the past 20 years, and when they have the latitude to build

early intervention programs, they can use those to really support their

families and address issues specifically around trauma and mental

health that are so likely to be exploited and used as a way to control

and profit off of Native people and instead create healthy families.

Callow is working with Susan Burch, a professor of American

studies at Middlebury College, and Juliet Larkin-Gilmore, a postdoctoral

fellow in the American Indian Studies Program at the University of

Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, on a special edition of Disabilities

Studies Quarterly that’s focused on Indigenous health and disability in

the past, present and future.

As part of the effort, the team invited people from across

the country to submit questions, ideas and thoughts about what they

believe we can learn from Native communities around disability, health

and well-being. Submissions could be in many forms, from essays and

journal articles to art and poetry.

Ella Callow: We didn’t want to limit it to academic

voices. We wanted to open it up, and we wanted to open it up to Native

people, particularly, to tell us what they wanted to tell us about the

subject. It’s so important for Native people to have an agency, and for

Native disabled people to have an agency, because that’s what, for so

long, people have tried to take away from them.

So, I think the most hopeful thing is to see how much tribes and

tribal people have taken control of the narrative about disability and

history in Indian country and the future of it and are building these

programs, have built these programs, are running these programs on

reservation, off reservation. And what we’ve seen submitted is amazing.

The way people are able to talk about this, want to talk about this

subject is really really heartening.

To learn more about Indigenous health and disability, check

out the special edition of Disabilities Studies Quarterly, to be

published in the summer of 2021.

For Berkeley News, I’m Anne Brice.

You can subscribe to this podcast, Fiat Vox, spelled F-I-A-T V-O-X, and give us a rating, on your favorite listening app. Also, check out our other podcast, Berkeley Talks, that features lectures and conversations at UC Berkeley.

You can find all of our podcast episodes on Berkeley News at news.berkeley.edu/podcasts.

Additional sources for this article:

- “In South Dakota, Officials Defied a Federal Judge and Took Indian Kids Away From Their Parents in Rigged Proceedings,” by Stephen Pevar, ACLU, Feb. 22, 2017

- “South Dakota v. Native American Parents: Why Are Children Being Separated From Their Families in Pennington County?” by Rebecca Buckwalter-Poza, Pacific Standard, May 3, 2017 (updated), April 1, 2014 (originally published)