On July 16, a brigade of cars and motorcycles crossed over the

Missouri River via the Chief Standing Bear Bridge. Their arrival in

South Dakota marked the conclusion of a three-day journey to return the remains of nine children to

the Rosebud Sioux Indian Reservation more than 140 years after the

children died at Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Carlisle, Pa.

The remains of a tenth child were returned to the Aleutian people in Alaska in June. During the 10 exhumations, a set of unidentified remains was also uncovered.

According to the Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center of nearby Dickinson College, there are known to be more than 180 graves at the Carlisle Indian School Cemetery. But as the Anchorage Daily News reports,

“The true number may never be known, historians say, given poor record

keeping, sloppy burial practices and the relocation in 1927 of a

cemetery so that a parking lot could be constructed.” Some of the graves

contain errors in both children’s names and their tribes.

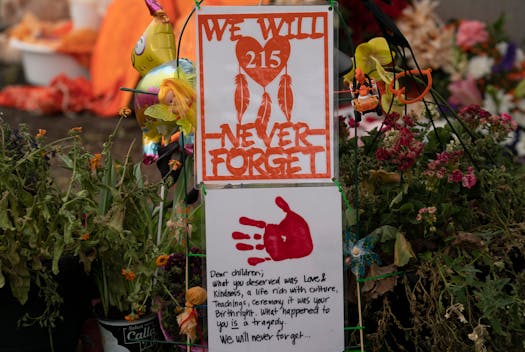

These recent exhumations follow the discovery of hundreds of unmarked graves in residential schools in Canada in June.

For

Indigenous communities, the existence of these schools and the abuse,

neglect, and murder committed within them are not new; Indigenous

communities have been aware of — and harmed by — boarding schools, many

of them run by Christian groups, for generations. And though Indigenous

people have ideas about how Christian communities can atone for their

involvement in the schools, many are not sure Christians are willing to

listen.

The Christian legacy

For Rev. Jim Bear Jacobs,

a citizen of the Stockbridge-Munsee Mohican nation and co-director of

racial justice for Minnesota Council of Churches, the fact that there’s a

graveyard attached to any school is unconscionable.

“Christians

sometimes want me to acknowledge the good intentions of the boarding

schools at the time,” said Jacobs, whose great grandfather was taken to

Carlisle. Jacobs finds such attitudes dismissive. “There’s a graveyard

attached to a school. At what point does that become OK? They were

forcibly taken from their families and they died. Regardless of what the

cause of death was, their bodies were never returned to their families.

These families are left devastated not knowing where their child is.

There’s no justification of that at all.”

Opened in 1879, the Carlisle Indian Industrial School was the first boarding school

in the United States that housed Indigenous children in an

off-reservation setting, far from their homes. In 1891, the U.S. passed a

compulsory attendance law that

required Indigenous children to go to the schools. The Carlisle school

eventually served as the blueprint for over 300 boarding schools for

Indigenous children across the U.S. as well as a similar program in

Canada

While the U.S. government opened 25 federal off-reservation boarding schools, more than 300 other schools were run by Christian groups with support from the government.

Upon

arrival, the schools forced students to cut their long hair, a

significant element of Indigenous faith and culture. The schools gave

children English names and forbade them to speak their native language.

In short, the church-run schools worked in cooperation with the

government to strip the children of their spiritual and cultural

practices and replace them with Christianity.

Some children were also exploited for free labor: They were sent to farm or perform housecleaning for local non-Natives. There are numerous reports of children at these schools being underfed, malnourished, and sick.

Dr.

Tink Tinker, a citizen of the Osage nation and professor emeritus of

American Indian cultures and religious traditions at Iliff School of

Theology, said that people in the United States don’t want to know “that

they killed Indians, cheated Indians, and stole land in order to create

this romantic experiment called the United States.”

“Americans

don’t want to know that children at boarding schools were fed a diet

that put them at great risk of disease,” Tinker told Sojourners. “What

the boarding schools demonstrate is that genocide was planned and

supported by the state, that is the federal government of the United

States.”

This is not news

While the

existenece of Indigenous boarding schools has largely been erased from

U.S. history, Indigenous people have been advocating for greater

truth-telling for decades. And they hope change is coming.

On

June 22, following the discovery of mass graves of Indigenous children

at Canadian residential schools, Deb Haaland, the U.S. Secretary of the

Interior, announced the creation of a Federal Indian Boarding School

Initiative to conduct a comprehensive review of the troubled legacy of

federal boarding school policies in the United States.

“The

Interior Department will address the inter-generational impact of Indian

boarding schools to shed light on the unspoken traumas of the past, no

matter how hard it will be,” Haaland said to the National Congress of American Indians.

“I know that this process will be long and difficult. I know that this

process will be painful. It won’t undo the heartbreak and loss we feel.

But only by acknowledging the past can we work toward a future that

we’re all proud to embrace.” Haaland is a member of the Laguna Pueblo;

her great-grandfather attended the Carlisle school.

Colette

Yellow Robe, a citizen of the Northern Cheyenne, grew up knowing about

boarding schools. Her mother survived boarding school and her

grandfather attended and survived Carlisle. In April, she said at least

one of her family members died under suspicious circumstances at a boarding school.

“We knew this was there, the cover-up of the death or murders,” Yellow Robe told Sojourners.

“When some of us went to high school, some

went to the boarding schools that are still open. Or historically you

just knew someone’s family who went to boarding school,” Yellow Robe

said. “It’s common. It’s a part of everyday existence. It’s like driving

by a national park: It’s just there.” Though attendance is no longer

mandatory, the U.S. still runs several boarding schools for Indigenous children.

Ruth

Hopkins, a Dakota and Lakota Sioux writer and former tribal judge, told

Sojourners her father was abducted and taken to a boarding school when

he was still nursing. “My whole life I've known about it. I’ve heard

different things spoken about in hushed tones,” she said.

Hopkins

said that the schools were forced upon Indigenous communities: families

who refused to send their children to the schools could be denied treaty rations or sent to jail. In many cases, children were abducted

from their homes by nuns and priests. To this day, Hopkins said,

Indigenous people are wary of outsiders or white people on reservations.

“If

they see outsiders coming, or white people coming, they don’t want them

to be around their children or see their children. That’s from boarding

schools, because they used to come and take peoples’ kids,” Hopkins

said. One of her grandmothers used to hide one of her children every

time a stranger came onto her property. The rest of her children were

brought to boarding schools.

Now, the legacy of boarding schools

affects everything from her community’s lack of knowledge of their

native language to how Hopkins folds her towels: the way her father was

taught at boarding school. It’s a legacy of trauma.

“You have

all of these people who were put through extreme abuse and neglect,”

Hopkins said. “You have people who didn’t really learn how to parent

correctly. And they have all of these missing pieces in them from their

culture and their language being taken away.”

Going forward

Indigenous people have suggestions for how, after centuries of abuse, Christians can begin to make restitution for these crimes.

The experts interviewed for this piece hope that Christians will advocate against pipelines, many of which directly violate treaty rights between the U.S. government and Indigenous communities.

As

Tinker put it, Indigenous communities need non-Natives “to become

allies in the Indian struggle for freedom” by physically standing up for

Indigenous dignity, as some did at the Dakota Access Pipeline protest

in 2016 and 2017. He implores Canada and the United States “to resist

the military industrial complex and its fossil fuel subsidiary as they

try to lay pipelines across Indian land or close enough to Indian land

to threaten Indian water supply.”

Jacobs, who also serves as a

parish associate at Church of All Nations Presbyterian Church in

Columbia Heights, Minn., is calling for reparations for Indigenous

people. He maintains that every predominantly white church in this

country should have a line in their budget that is dedicated to local

Indigenous language and cultural reclamation projects, “and it should be

a significant amount of the annual budget.”

“It should be a

significant amount because, for Indigenous people, the legacy of

boarding schools is that it cost us everything,” Jacobs said. “We lost

our language. We lost ties with our families and our culture. At a

minimum, I tell churches that the work of repair looks like them paying a

price to help try and mitigate and reverse some of the damage that came

out of those boarding schools.”

However necessary, reparations and anti-fracking advocacy might be a big leap, especially for U.S. churches that have not claimed responsibility for

the boarding schools or the murders of Indigenous children within them.

The national Native American Boarding School Healing coalition lists 14 different religious groups that

operated boarding schools in the United States, including Roman

Catholics as well as Presbyterian, Quaker, Episcopal, Methodist,

Baptist, Mennonite, and other Protestant denominations.

There’s some hope this is changing: While the Vatican has refused to release residential school records, two religious communities in Canada have released records as well as the United Church of Canada.

In

December, the pope is scheduled to meet with representatives of

Canada’s three biggest Indigenous groups — the First Nations, the Métis,

and the Inuit — to “apologize for the church’s role in operating

schools that abused and forcibly assimilated generations of Indigenous

children.” A statement from the Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops said

that Pope Francis is “deeply committed to hearing directly from

Indigenous Peoples, expressing his heartfelt closeness, addressing the

impact of colonization and the role of the Church in the residential

school system, in the hopes of responding to the suffering of Indigenous

Peoples and the ongoing effects of intergenerational trauma.”

Christian

organizations would do well to not only tell the truth about boarding

schools but to release any information pertaining to them.

Amber

Starks, an Afro-Indigenous activist who is a citizen of the Muscogee

(Creek) Nation, said that acknowledgement looks like an honest verbal

acknowledgement and concrete action, not a halfhearted committee or

one-time donation.

“There’s a lot of talk about restitution, but

it just doesn’t seem authentic,” Starks said. “It doesn’t seem like the

church as an institution genuinely cares about the ongoing harm of its

participation in colonialism, in imperialism, and in genocide. Since it

doesn’t care about those things, it doesn’t care about the healing that

has to go into that.”

For Native communities, it’s clear that

Christians are both complicit in and beneficiaries of the legacy of U.S.

boarding schools. Will Christians acknowledge this reality?

Starks hopes so.

“Be

willing to be exposed for the wrong that you’ve done,” Starks said. “It

shouldn’t take years to return the bodies of our relatives to tribes so

that tribes can bury them in accordance with tradition and protocol.

Where’s the humanity in that? Why would it take that long?”

“There

are all of these lives buried underneath this place that you call holy

ground,” she continued. “And it’s not holy. It’s been desecrated because

you committed genocide.”

“Our

government stands shoulder to shoulder with Indigenous partners as we

support community-directed work to identify and commemorate Indigenous

Residential School sites across the province. Today’s investment in the

Woodland Cultural Centre is critical to the important work being done by

Six Nations of the Grand River to build a national resource to support

public education and centre for healing for the community.” – The Honourable Greg Rickford, Ontario’s Minister of Indigenous Affairs

“Our

government stands shoulder to shoulder with Indigenous partners as we

support community-directed work to identify and commemorate Indigenous

Residential School sites across the province. Today’s investment in the

Woodland Cultural Centre is critical to the important work being done by

Six Nations of the Grand River to build a national resource to support

public education and centre for healing for the community.” – The Honourable Greg Rickford, Ontario’s Minister of Indigenous Affairs

![Tk'emlups te Secwepemc Chief Rosanne Casimir speaks ahead of the release of findings on 215 unmarked graves discovered at Kamloops Indian Residential School in Kamloops, British Columbia, Canada, July 15, 2021 [Jennifer Gauthier/Reuters]](https://www.aljazeera.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/2021-07-15T185644Z_664108146_RC2XKO9GTC0J_RTRMADP_3_CANADA-INDIGENOUS-CHILDREN.jpg?resize=770%2C513)

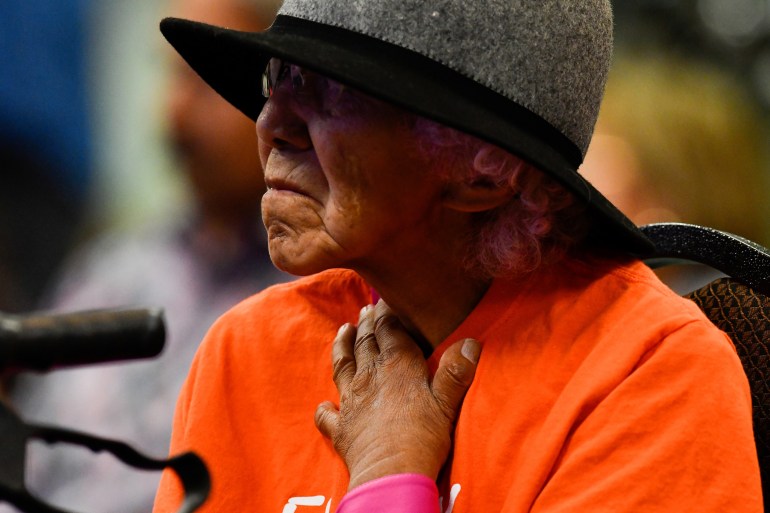

Residential

school survivor Mona Jules takes part in a presentation of the findings

on 215 unmarked graves discovered at Kamloops Indian Residential School

in Kamloops, British Columbia, Canada, July 15, 2021 [Jennifer

Gauthier/Reuters]

Residential

school survivor Mona Jules takes part in a presentation of the findings

on 215 unmarked graves discovered at Kamloops Indian Residential School

in Kamloops, British Columbia, Canada, July 15, 2021 [Jennifer

Gauthier/Reuters]