School was operated by the federal government between 1884 and 1934 and was known for brutal punishments and hard labour

Researchers say they have identified more than 100 students who died at a harsh residential school for Native Americans in Genoa, Nebraska. The search for the cemetery where many are believed to be buried continues.

The Genoa US Indian School was operated by the federal government between 1884 and 1934. Brutal punishments and hard labour were commonplace for students, large numbers of whom were removed from their families and homelands against their will, prohibited from speaking tribal languages and forced to convert to Christianity in an effort to subdue or eliminate Indian culture.

The announcement from the Genoa Indian School Digital Reconciliation Project, a collaboration between the University of Nebraska-Lincoln (UNL), the Genoa US Indian School Foundation and descendants and representatives from five Nebraska tribes, is among the most significant developments since the project began in 2017.

The names of 102 deceased students were gathered from sources including newspaper archives and school newsletters, according to the researchers who say official records were destroyed or scattered when the school closed.

While some names are likely to be duplicates, the death toll from the school which enrolled thousands from more than 40 tribal nations in its 50-year history is probably far higher, said Margaret Jacobs, professor of history at UNL and project co-director.

She said the names would be released after consultation with tribal leaders and after efforts to trace living relatives of the deceased were exhausted.

“These children died at the school,” Jacobs told the Omaha World-Herald. “They didn’t get a chance to go home. I think that the descendants deserve to know what happened to their ancestors.”

Some of the students, aged four to 22, died in accidents, by drowning or by shooting and in one case reportedly after being hit by a freight train. But most died from disease. Tuberculosis and pneumonia were rife in the federal Indian school system set up in the 1860s with the intention of educating tribal youth in the English language.

The system took a dark turn in 1879 when a US army brigadier general, Richard Henry Pratt, founded Pennsylvania’s Carlisle Indian Industrial School, the first off-reservation boarding school for Native Americans, with the motto: “Kill the Indian, save the man.”

In a harsh era, thousands of children were forced to leave their families and travel to schools in other states, to “remove them from tribal influences”. Many teachers forced students to speak only English, and many schools imposed military style rules. Braids were cut off and students given “white” names.

Some graduates said they benefited from the experience and educational opportunities they would not otherwise have received, but numerous other accounts record harsh discipline, abuse and exploitation, the Genoa project says.

One descendant claimed his great-grandmother was blinded while a student at Genoa, likely by having lye soap rubbed into her eyes as a punishment.

The search for the school’s cemetery is continuing in partnership with the Nebraska Commission on Indian Affairs and the state archaeology office. Maps from the 1920s marked a plot of the 640-acre campus where it was believed to exist but ground-penetrating radar has failed to find any graves, project leaders said.

“If we’re not able to find them, I think we need to do something to recognize that they lost their lives there,” Judi gaiashkibos, a citizen of the Ponca Tribe and the commission’s executive director, told the World-Herald.

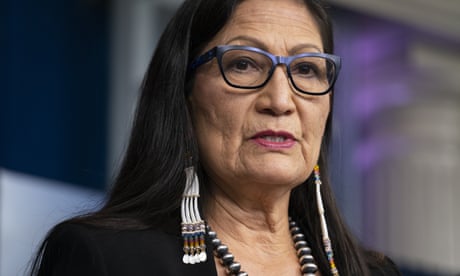

The troubled legacy of Native American boarding schools became a focus of Joe Biden’s administration in June when the interior secretary, Deb Haaland, announced an investigation into “horrific assimilation policies”.

It followed the discovery of the graves of more than 200 children at an Indigenous residential school in Canada in May. In the US, Haaland, a Laguna Pueblo tribe member, said her maternal grandparents were among those forcibly removed, her grandfather to the Carlisle school.

“Many Americans may be alarmed to learn that the United States has a history of taking Native children from their families in an effort to eradicate our culture and erase us as a people,” Haaland wrote in an opinion piece in the Washington Post.

“It is a history that we must learn from if our country is to heal from this tragic era.”

The Federal Indian Boarding School Truth Initiative will investigate allegations of abuse and assist efforts to locate burial sites.

“I’m looking to see something good come out of this,” gaiashkibos said. “Perhaps we will find some way to restore language, to restore some of the culture that was stripped from us.

“Everyone needs to learn the stories and say, ‘America did this and we can do better’.” SOURCE

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please: Share your reaction, your thoughts, and your opinions. Be passionate, be unapologetic. Offensive remarks will not be published. We are getting more and more spam. Comments will be monitored.

Use the comment form at the bottom of this website which is private and sent direct to Trace.