Buildings at the Carlisle War College that once were the Carlisle Indian School, March 22, 2016. James Robinson, PennLive.com

By Red Power Media, Staff | May 6, 2016

Nearly 200 American Indian children perished at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School

For more than 100 years, American Indian

children have been buried at Carlisle, the school that sought to cleanse

their “savage nature” by erasing their names, language, customs,

religions, and family ties.

Between 1879 and 1918, more than 10,000 American Indian children were housed at the

Carlisle Indian Industrial School, the federal government’s flagship boarding school based on a strict military model.

The children

were

stripped of all tribal traditions. Their native names were changed to

European names and they were forced to adopt the traditions of white

America.

Nearly 200 of the children perished at the

school, most from diseases like tuberculosis or consumption. Their

remains were never returned to their families. The children’s final

resting place is on the grounds of what used to be the boarding school

and is now part of the U.S. Army War College in Carlisle.

Grave-sites at Carlisle cemetery are often decorated by visitors with small stuffed animals, dreamcatchers and toys.

Now there’s a chance that some will be sent home to their tribes.

Patrick Hallinan, the head of Army cemeteries said in an

interview

that he’s open to meeting American Indian demands to repatriate

children’s remains, provided talks on the matter prove fruitful and all

regulations are met.

This marks a reversal for the Army, which in winter denied a Rosebud Sioux request to return 10 tribal children to South Dakota.

Now the Army confirms it will send two

officials to Rosebud on May 10, to begin formal government-to-government

consultations with the Sioux, the Northern Arapaho of Wyoming, and a

third tribe that now seeks the return of its people, the Northern

Cheyenne of Montana.

“I think things are going to happen,” said

Russell Eagle Bear, the Rosebud historic-preservation officer. “I’m

hoping they’re going to tell us they’re ready to work with us and let

our relatives go.”

If that occurs, he said, an intended summer

tribal pilgrimage to Carlisle could become an advance party to plan the

return of Sioux remains.

The nearly 200 children that lie in the

Carlisle cemetery were among thousands taken from native families in the

West, spirited a thousand miles to the East, and forced through a

wrenching experiment in assimilation.

Today many American Indians view what took place at Carlisle as genocide.

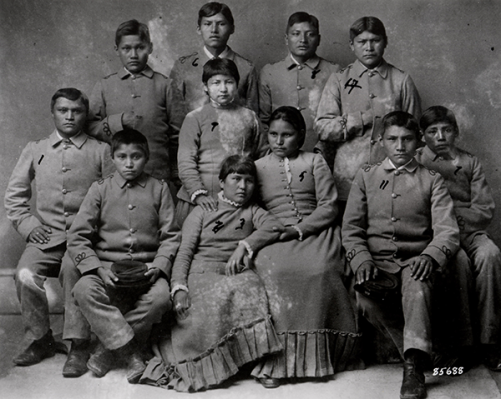

American Indian children upon arrival at Carlisle Indian Industrial School.

American Indian children four months after their arrival at Carlisle Indian Industrial School.

Hallinan says, the decision to return remains from Carlisle to Rosebud or elsewhere, rests with him.

“If the tribes are interested and this is

something they want to do, we would be supportive to see that

accomplished,” Hallinan said. “We look forward to working with the

tribes, and we think that once we sit down and consult with them, there

should be a positive outcome for all involved.”

He plans to send staff to two American

Indian conferences this year, to see if other tribes wish to discuss the

status of their ancestors’ remains.

While the Army plans to send two people on

May 10, dozens could attend from Indian nations. Leaders of the Rosebud

Sioux, Northern Arapaho, Cheyenne River Sioux, Northern Cheyenne,

Standing Rock Sioux and Sisseton-Wahpeton Oyate Tribes will meet on

Tuesday, in Rosebud, South Dakota with representatives from the federal

government and the U.S. Army to begin negotiations over the repatriation

of the children’s remains.

All six tribes intend to have people there,

and the Rosebud Sioux will bring lawyers, political leaders, and tribal

staff. South Dakota’s senators and congresswoman will send

representatives.

This month’s meeting in Rosebud could

portend a major step forward on an issue that torments many native

peoples. It comes amid an outpouring of interest and awareness that

followed a March 20 story in the Inquirer.

Carlisle opened in 1879 as the first federal

Indian boarding school, spawning a fleet of successors that embraced

the motto, “Kill the Indian, save the man.”

At Carlisle, children who spoke their native

language could be beaten, while overcrowding and malnourishment

weakened students, making them vulnerable to epidemics that swept the

school.

Today many Indian researchers and activists

refer to those who attended Carlisle and similar institutions as

“boarding school survivors.” They say collective trauma and grief

contributes to the devastating social ills that plague tribal

communities.

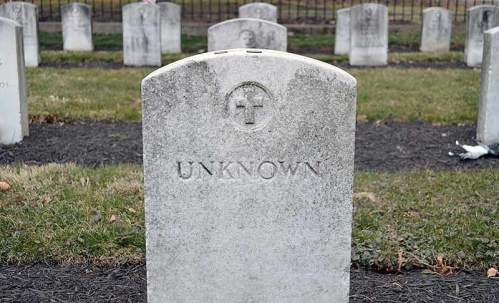

Carlisle cemetery grave marked “Unknown.”

Officially the Carlisle cemetery contains

186 graves. Thirteen are marked “Unknown.” Many of the headstones bear

names but no birth or death dates.

For approximately three decades

beginning in the latter part of the 19th century, the federal

government, in an effort to “tame the savage” and assimilate them into

the dominant white culture, uprooted close to a million American Indian

children from their reservation tribal homes, transporting them

thousands of miles across the country to boarding schools.