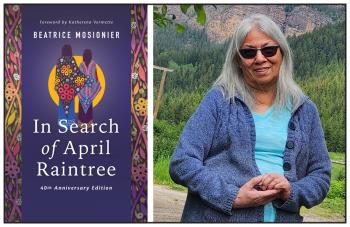

Little did Beatrice Mosionier expect that her first novel, In Search of April Raintree, would have such a profound impact on Indigenous readership.

But perhaps she should have.

When she was seven or eight years old, she was working in the

basement of her second foster home in St. Norbert, a suburb of Winnipeg.

“I got this really powerful knowledge, and it was that I would have

these three animals that would guide me: The wolf, the bear and the

cougar,” said Mosionier, a Plains Métis woman.

“Later when I finally started talking about it with other people, I

was told about guide animals, spirit animals, that give you strength…

And it was like I was going to do something special in my life.”

She forgot about the spirit animals until she hit her thirties. In

1980, when Mosionier was 31, her oldest sister Katherine committed

suicide. Sixteen years before, her other sister Vivian had taken her own

life.

“It was just like things were shifting inside of me. I think that's

probably how I came to decide I was going to write a book, and I think

that was what led up to this,” said Mosionier.

But when she wrote In Search of April Raintree in 1983, Mosionier never believed it would be published.

Forty years later, Highwater Press is releasing a special 40th anniversary edition of the novel.

Mosionier and her siblings were apprehended in the earliest years of

the Sixties Scoop, which saw an estimated 20,000 or more Indigenous

children removed from their homes between 1951 and 1984.

Mosionier was taken at the age of three by the Children’s Aid Society

of Winnipeg. The loss that resulted from that action was the story she

told in the lives of April Raintree and the fictional younger sister

Cheryl.

It was a story that resonated mightily with Métis and First Nations

readers, as noted in words of praise that accompany the anniversary

edition.

“In Search of April Raintree was the first book I read that

spoke to the Indigenous experience, and it changed me for the better,”

wrote Governor General Award winner David A. Robertson.

“I could feel it in my blood memory. Because it was tender and

brutal, authentic and unapologetic, heartbreaking and hopeful,” wrote

Rosanna Deerchild, host of CBC Radio One’s Unreserved.

“Reading Beatrice Mosionier’s seminal novel was lifechanging. As a

young Indigenous woman, it was the first time I felt seen,” wrote

Manitoba NDP MLA Nahanni Fontaine.

Those words make Mosionier feel “really humbled.”

She wrote the book “to find answers,” spurred on by the deaths of her sisters.

“I think that’s really hard on a parent…When you lose a child to

suicide and then you lose a second child to suicide, there's something

majorly wrong,” said Mosionier.

In writing the novel, Mosionier gained personal insight into her own family and into the larger picture of being Métis.

“I was raised in white foster homes since I was three years old. I

wasn't connected to—back then we used to call it the Native—Native

people,” she said.

“I did get more understandings about the why and everything. Because

when I grew up, we didn't know words like ‘oppression’ and ‘racism’ and

all the things like that when we're in school…We knew people don't like

us, but we don't know why it could be. You know, because we're brownish

and because we're foster kids.”

Along with telling the personal stories of April and Cheryl,

heartbreaking and uplifting, in turn, Mosionier used Cheryl’s essay

writing talent in the book to tell the wider proud Métis history.

Mosionier had to research for Cheryl’s essays. She started watching a

Winnipeg television series that had interviews with Indigenous people.

Her next-door neighbour, who wasn’t Indigenous, gave her a book by

Heather Robertson titled Reservations are for Indians.

“I read that book and then I had a fairly good sense, because back

then we didn't have computers and Google and all of that,” she said.

After her book was published, she discovered that St. Norbert had a

rich Métis history. She also learned that her father used to play the

fiddle.

“I didn't know anything about that. I didn't know. I just didn't know anything positive,” said Mosionier.

While there are brutal scenes in the novel, perhaps the most haunting

scene comes in April’s realization near the end, which echoes the words

of her broken father: “Baby Anna. Such a small part of our lives. Yet

she had changed our lives the most.”

It is when Baby Anna is sick and goes to the hospital that April and

Cheryl are wrongfully apprehended, and that single action sets in motion

everything that follows.

Forty years later, Indigenous children are still being apprehended at a disproportionate rate.

“In Search of April Raintree is one of the all-time great

works of Indigenous literature, and it is still as vital and relevant

today as it was forty years ago,” wrote Dr. Warren Cariou, a professor

at the University of Manitoba.

Mosionier agrees with Cariou’s observation about the relevance of her novel.

But, “I kind of feel sometimes that (the novel) didn't do its job

because a lot has changed but a lot has not changed, and sometimes you

think it's getting worse,” she said.

If her novel opened the gates for other Indigenous authors, Mosionier says, “I feel good about that.”

And she encourages Indigenous authors to keep doing their strong work, many of whom are now being recognized with awards.

As for her spirit animals who told her she would do something special in her life, Mosionier firmly believes writing In Search of April Raintree was that act.

The special 40th anniversary edition of the novel will be released by Highwater Press in September.

Local Journalism Initiative Reporters are supported by a financial contribution made by the Government of Canada. SOURCE

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(741x256:743x258):format(webp)/Custody-battle-072523-tout2-6ae541d56787418387bf606986a7ea42.jpg)