SOURCE

“I feel shame and pain. I ask forgiveness of God,” Pope Francis said

on Friday as he apologized for the “deplorable” abuses of Canada’s First

Nations children.

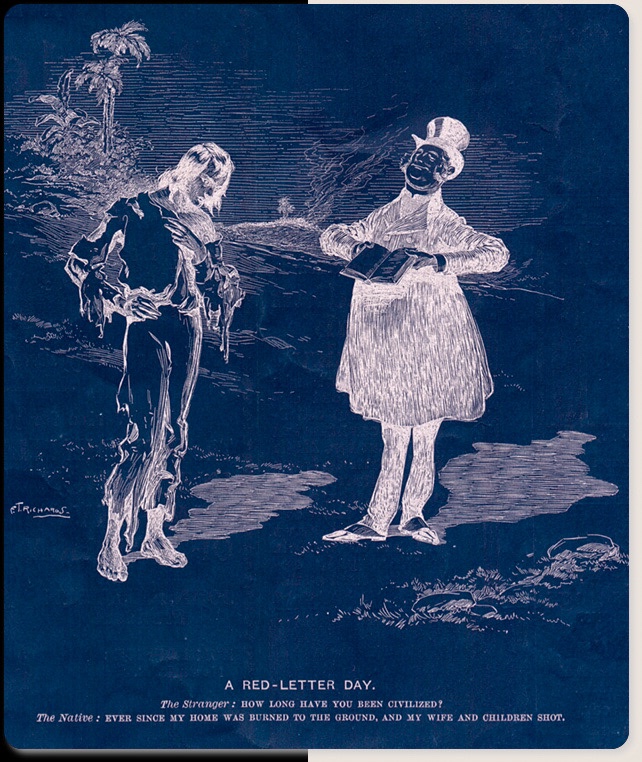

Between the 1880s and the 1990s, the government ran a system of

compulsory boarding schools which a National Truth and Reconciliation

Commission (TRC) recently dubbed ‘cultural genocide’,” The New York

Times reported. The Catholic church operated about 70 percent of those

schools, where about 150,000 children were placed and “where abuse, both

physical and sexual, was widespread, along with neglect and disease,”

The Times said. A former judge, Murray Sinclair, who headed the

commission, estimated that at least 6,000 children went missing.

The TRC, established as part of a government apology and settlement

over the schools, concluded that at least 4,100 students died from

mistreatment, neglect, disease or accident. The Tk’emlups te Secwepemc

First Nation in British Columbia, using ground penetrating radar,

discovered the remains of 215 of them buried near the Kamloops Indian

Residential School which opened in 1890 and closed in the late 1970s,

The Times reported. “It’s a harsh reality and it’s our truth, it’s our

history,” Chief Rosanne Casimir told a news conference.

Children were also placed with non-Native families, a policy which

Ontario Superior Court Justice Edward Belobaba denounced as he ruled in a

class action lawsuit, The Guardian reported. “There is … no dispute

that great harm was done,” Belobaba wrote. “The ‘scooped’ children lost

contact with their families. They lost their aboriginal language,

culture and identity. Neither the children nor their foster or adoptive

parents were given information about the children’s aboriginal heritage

or about the various educational and other benefits that they were

entitled to receive. The removed children vanished ‘scarcely without a

trace’.”

In Australia, Kevin Rudd, as prime minister, apologized in 2008 for

this "great stain on our nation’s soul." He was referring to more than

100,000 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children being placed in

institutions or foster homes or adopted by nonIndigenous families

between 1900 and 1970.

New Zealand tried to “civilize” Māori children, starting in 1840.

“Boarding schools initially taught in the Māori language but soon

qualified for subsidies only if lessons were in English. By 1960, only

26 percent of children could still speak their native language,” the

Toronto Globe and Mail reported.

Denmark’s Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen apologized for the

treatment of 22 Inuit children from Greenland, then a Danish colony,

more than 70 years ago, Agence France Press reported. Frederiksen told

the six survivors at a ceremony in the Danish capital Copenhagen, “What

you were subjected to was terrible. It was inhumane. It was unfair. And

it was heartless.”

Norway, Sweden and Finland are supporting initiatives to protect the

culture of the Sami people living in Sápmi — formerly Lapland —

following efforts to force them to culturally assimilate, The Guardian

reported.

In the United States, the Trump administration’s seizing of 2,300

refugee children from their parents recalled a history of African and

Indigenous family separation. The Washington Post recalled this tweet

from the African American Research Collaborative: “Official US policy.

Until 1865, rip African American children from their parents. From 1870s

to 1970s, rip Native American children from their parents. Now, rip

children of immigrants and refugees from their parents.” The Post drew

attention to “The Weeping Time” exhibit at the Smithsonian’s National

Museum of African American History and Culture documenting the story of

children sold away from their enslaved families.

The government sent thousands of Indigenous children to government or

government-funded, church-run “Indian schools” between the 1800s and

the 1970s. Richard Pratt, who founded the first one, the Carlisle Indian

School in Pennsylvania on Nov. 1, 1879, described his philosophy as:

“All the Indian there is in the race should be dead. Kill the Indian in

him and save the man.”

“While the government believed a white youth’s ‘moral character and

habits are already formed and welldefined, when he leaves for school, a

Indigenous youth was thought to be ‘born a savage and raised in an

atmosphere of superstition and ignorance’,” The Equal Justice Initiative

reported. “The government believed that ‘if [an Indigenous child] is to

rise from his low estate the germs of a nobler existence must be

implanted in him and cultivated.’”

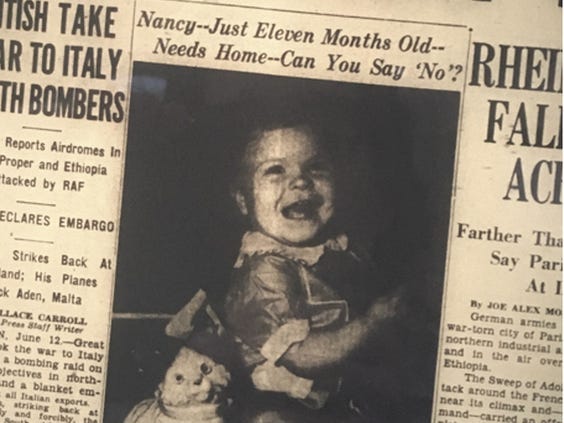

As the boarding schools began closing, the government launched the

Indian Adoption Project to promote European American adoption of

Indigenous children, Vox reported. “The data showed that 25 to 35

percent of Native children around the country were being taken from

their homes, and that 85 to 95 percent of those kids ended up in

non-Native homes or institutions,” Vox stated.

Elizabeth Williams, who had been sold twice since she last saw her

children, placed an ad in the Christian Recorder newspaper in

Philadelphia in 1866 to try to locate them, The Post said. And Sandy

White Hawk, a Sicangu Lakota adoptee from the Rosebud Reservation in

South Dakota, founded the First Nations Repatriation Institute to help

adoptees reunite with their tribes and families.

WGBH noted in a 2015 documentary that Maine had set up its own TRC –

an approach which South Africa started in 1995 to try to forge unity

after apartheid ended. The commission heard Indigenous testimony such as

this: “All we did was beg for our foster mothers to hug us and say they

loved us. My baby sister and I sat in a tub of bleach one time trying

to convince each other that we’re getting white.”

The struggle continues with a federal lawsuit challenging as racially

discriminatory the 1978 Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA), which deals

with child separation, filed by a European American couple in Texas,

joined by their state, Indiana and Louisiana. The National Indian Child

Welfare Association says the law addresses a crisis affecting Indigenous

children, families and tribes. Invalidating the ICWA, its supporters

say, would have far-reaching consequences for Indigenous peoples,

including the issue of tribal sovereignty.

Pratt’s racism and White Hawk’s lament notwithstanding, it is hard to

miss the defiance in the song “Drums” written by Peter LaFarge which

Johhny Cash sang 58 years ago:

“And when they think that they’d changed me

Cut my hair to meet their needs

Will they think I’m white or Indian

Quarter blood or just half breed

Let me tell you Mr. teacher

When you say you’ll make me right

In five hundred years of fighting

Not one Indian turned white.”

/https://www.thestar.com/content/dam/thestar/news/canada/2022/04/01/popes-apology-a-powerful-gesture-but-unlikely-to-affect-court-cases-in-canada-experts-say/pope.jpg)