|

| PHOTO: Author Joseph Lee. (Photo/Aslan Chalom) |

By Shaun Griswold | Yahoo News

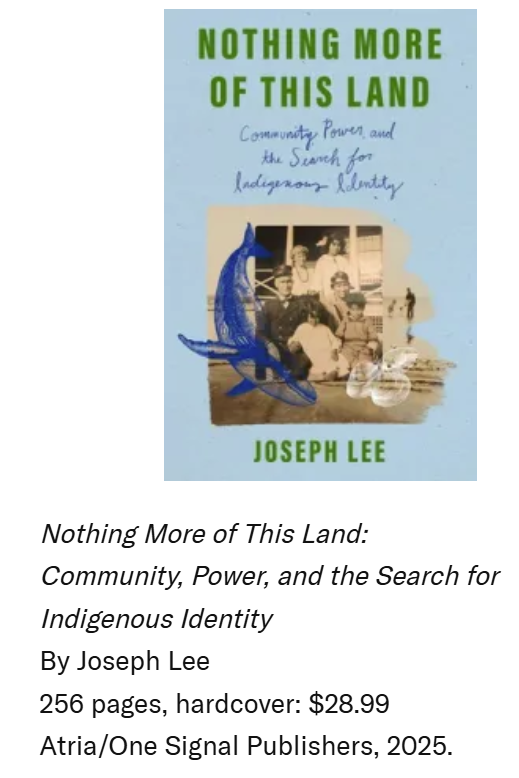

Summer memories of running with cousins in Zuni mud — all the weekends I spent at my Auntie Paula’s home on the Zuni Pueblo — return as I read Joseph Lee’s book Nothing More of This Land: Community, Power, and the Search for Indigenous Identity.

A mixture of memoir, reportage and commentary, it documents Lee’s family history, describing how land and ancestry forged strong links to his Aquinnah Wampanoag home on Martha’s Vineyard. Lee’s stories echoed my own rez dirt memories, layers of loving Indigenous relationships with foundations deeper than any historical record.

[Editor's Note: This column originally appeared in "High Country News. Used with permission. All rights reserved.]

Lee spoke with High Country News before his book’s July 15 release.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

High Country News: Your book demonstrates how you and your family live as Indigenous people on colonized land. Can you introduce those experiences?

Joseph Lee: I’m a Wampanoag, and my family and my tribe is from Martha’s Vineyard. It’s a small island in the Northeast, known for being this fancy vacation place where presidents and movie stars go. I grew up spending summers at my grandparents’ house, and that was the original framing for the book: How I thought about being Indigenous and being Wampanoag was filtered through the experience of how people see Martha’s Vineyard, along with how people see Wampanoag people and Native folks in the Northeast: We were there when the pilgrims came, Mayflower, the first Thanksgiving, all of that.

That confused me, because what I was being told about being Indigenous didn’t really match up with the way I was experiencing it personally. I went to tribal summer camp, I went to our cranberry festival harvest. I did all these things, and none of it aligned with this version of stereotypical Nativeness, the disappeared Native gone in the past.

I was trying to make sense of the way that we’ve lived and the choices that we’ve made, and what is this going to look like in the future?

keep reading👇

HCN: The book speaks clearly about how you approach mixed heritage and background. How did you define Indigeneity in researching and writing this book?

JL: Indigenous identity, like many identities, is something that is so often defined by external sources, by outsiders, people telling us, “Here’s what you have to be, here’s what it means to be Native.” For a long time I internalized that, even though I rejected it. I didn’t want that to be the only way to be Native, but I couldn’t necessarily see another way beyond those external expectations or stereotypes.

I’d spent all this time thinking about defying stereotypes or being upset at these expectations, and I hadn’t spent enough time thinking about what it means to be Indigenous — what does that mean to me?

My dad’s family is from China and my mom’s mother is from Japan, and then my mom’s father is Wampanoag. So one of my four grandparents is Wampanoag. For a long time, I sort of saw those things as all separate. I felt like I had to talk about being Wampanoag in one box and one part of my life and being Asian in another part of my life. Ultimately, I realized that it’s all me, it’s all part of my life. I can’t separate those things.

HCN: Some of the book recreates or imagines your grandparents’ experiences. What was that like for you?

JL: It makes me feel closer to my grandparents and my family and my entire community. I grew up knowing three of my grandparents, but they passed away when I was fairly young. So most of my life, I haven’t been able to spend time with my grandparents. Recreating their lives, who they were, was a really special part of the book.

One of the best compliments I got is after my mom read it for the first time. She said that she felt I really captured her mom, my grandmother — somebody I knew as a child but wasn’t around anymore from a pretty young age. There was so much I didn’t know about her.

It’s a unique experience to go back and see them as young people and growing older and navigating the world — and, in many cases, navigating some of the same questions and challenges that I’m now navigating myself.

HCN: How did you share your research with your family?

JL: I think the question you’re asking is important — this question of the historical record and preserving and sharing information — because a lot of that has been lost, sometimes deliberately erased. There’s a lot of misinformation; Indigenous voices aren’t the most prominent ones when you look back through history, and so it’s important to surface those things. Just because Indigenous folks weren’t featured in all the history books doesn’t mean they weren’t saying things.

When I went back through my own tribe’s history, people had opinions and were writing and reading and researching and making art and doing all of these things. It was just an amazing experience to be able to go back through all those records. There was so much I didn’t know about my own tribe, my own family and my own community. I knew that information was out there, I just had to find it. Some of that was hard-copy records, some was oral history, talking to people, memories. It’s important to not value one of those over the other. I’m grateful that I have my parents and other family members and folks in the tribe I could lean on.

SOURCE: https://nativenewsonline.net/arts-entertainment/finding-your-ancestors-in-the-archives

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please: Share your reaction, your thoughts, and your opinions. Be passionate, be unapologetic. Offensive remarks will not be published. We are getting more and more spam. Comments will be monitored.

Use the comment form at the bottom of this website which is private and sent direct to Trace.