Erasure is how anti-Indigenous racism works by Rebecca Nagle

Read on SubstackHave you ever heard that icebreaker–if you had to pick one superpower, would you fly or be invisible? I always pick the power of flight. I already know what it’s like to be invisible. In this country, it is not a form of power.

Once, I was at a grassroots social justice convening in Florida. On a break while people made small talk, a white woman came up to me and said, “I thought we killed all of you.” As in, she thought Native Americans were extinct like the woolly mammoth. It is a bewildering stereotype to encounter. The stereotype that you no longer exist. 82% of adults in the U.S. cannot think of a single, living, famous Native person. 98% cannot name two.

When you scroll through your phone, read the news, or watch TV, statistically, it is very unlikely you will see a Native person. Of the 2,336 regular characters on TV from 1987 to 2009, only two were Native. A recurring character on Northern Exposure. And a contestant on the reality show Survivor.

On the rare occasion Native people are portrayed in the media, we live in the past. In one study, researchers typed “Native American” and “American Indian” into the Google image search bar. 95% of the results were “antiquated portraits.” Once, someone told me that, even though she didn’t believe that I was Native, she knew that my ancestors were. Conveniently for a country built on our land, all of the real Indians are dead and gone.

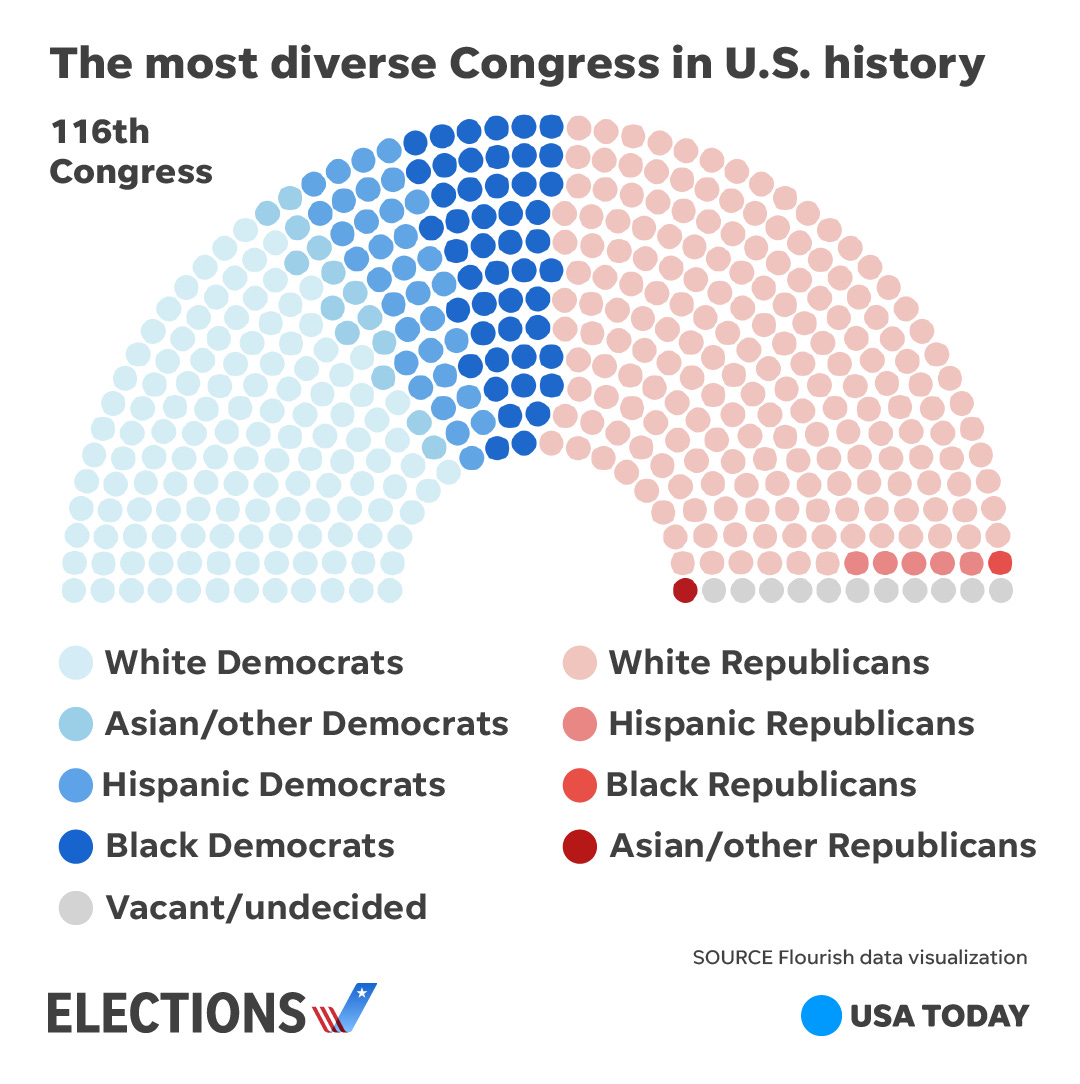

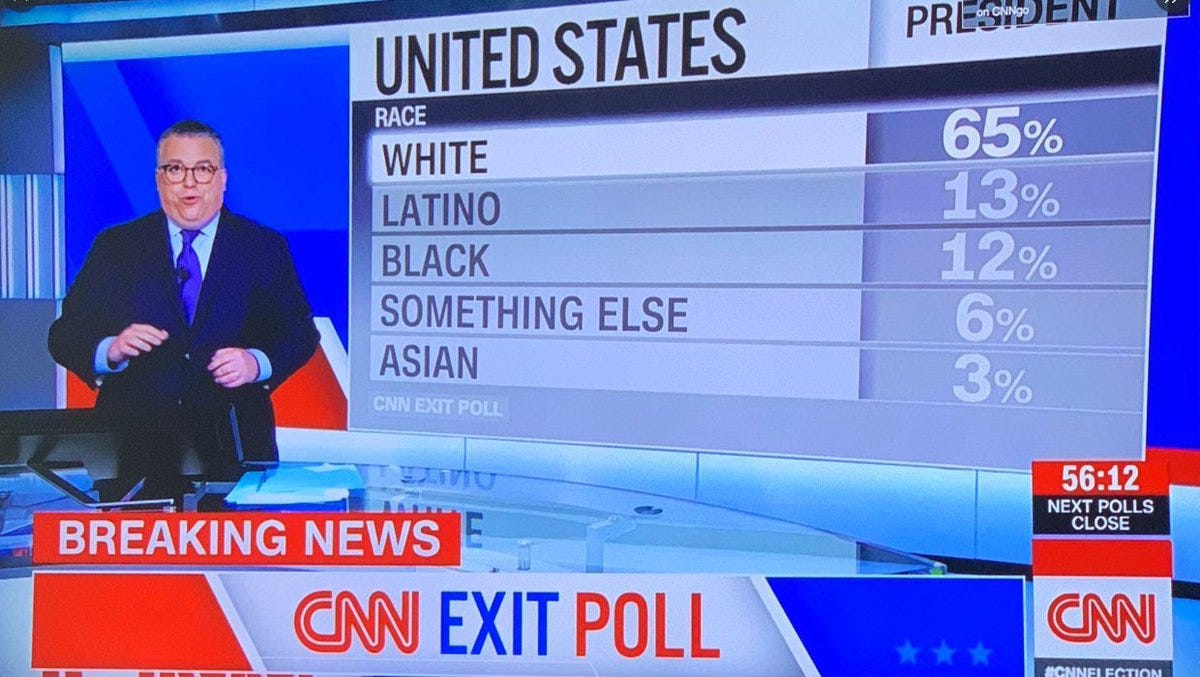

In 2018, U.S. voters elected the most diverse Congress in our country’s history. For the occasion, USA Today made an infographic. The 116th Congress included two Native women–the first ever elected to the body. In their infographic, USA Today put the Native representatives in the “other” category. In the 2020 election, Native voters helped Biden win the swing state of Arizona. On election night, CNN published an exit poll capturing how people voted in the state. On it, Native voters were called “something else.”

Native people are not simply left out of the story. We are written out.

We don’t learn about most people through direct social interactions, but from things like movies and the internet. I have never been to France, but I have an idea in my head that French people like wine and cheese. When a group is negatively represented, that can lead to stereotypes and prejudice, like the idea that women are bad at math. What Native people face is different. The media, pop culture, and school curriculum do not just represent us poorly. It represents almost never. Our existence is erased from the public eye. Americans don’t think about our absence. They don’t think about us at all.

This erasure harms Native folks. Our near-total absence from the media Americans consume creates a stubborn prejudice in the minds of non-Natives. Over time, they see us as less real and even less human. Research has found that less exposure to contemporary Native people correlates with more prejudice against us and less support for tribal sovereignty. One study found that the more contemporary Native people were omitted, the more participants agreed that the U.S. should nullify all treaties, eliminate all reservations, and abolish tribes’ right to self-govern. It is active erasure.

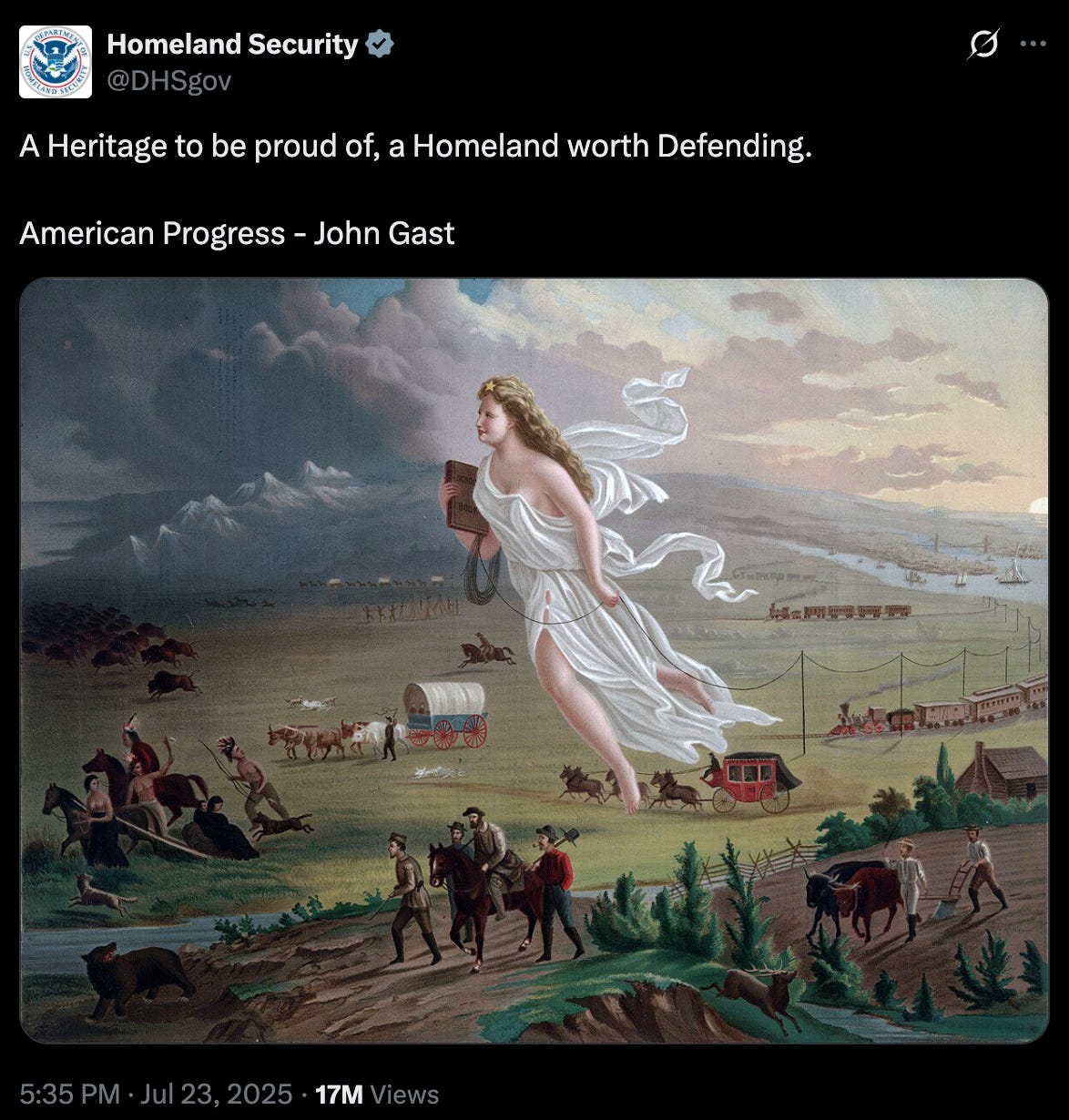

Last summer, Homeland Security posted a famous painting of manifest destiny on Twitter or X with the caption “a heritage to be proud of”. The image depicts an angelic, white woman floating above the open prairie. Below her, pioneers move onto the land, while Native Americans and wild animals disappear into the dark edge of the landscape. Zeteo, a new, left-leaning news organization, published an article about how the tweet was a dog whistle for white supremacy. I clicked on the article. It barely mentioned my community. Instead, it analyzed which letters the tweet had capitalized and how those letters corresponded to neo-Nazi slogans.

To expand West, the US Army rounded up Indigenous people by gunpoint and herded us into concentration camps. When Seminoles evaded capture, the army purchased bloodhounds. When the herded Choctaws were starving, the army sent rancid meat. At first, the Choctaws refused to eat it, but the army captain refused to give them other food. Later, he happily reported to his superiors that the people were so hungry they complied. When a Cheyenne and Arapahoe village handed over their guns and lived under a white flag of truce, the army gunned them down. Mothers dug holes into the riverbank to try and hide their children. After killing those women, soldiers cut out their genitals to keep as souvenirs. Like the Nazis did to the people they slaughtered, the Army Colonel in charge compared Indigenous people to lice. When members of Congress confronted that Colonel at a public hearing in downtown Denver, the crowd chanted “exterminate them!” That is how the U.S. expanded. Painting that violence as God‘s will is racist. We don’t need to find Hitler’s initials to understand why.

I am a journalist. I help make the news. For a long time, I thought it was my job to fix all this. To push back against the erasure. I thought the primary victims of invisibility were my community trapped behind the cloak. And then, Trump got reelected. This past year, I keep hearing the word unprecedented. As an Indigenous person, none of it feels unprecedented to me. Slowly, I came to realize there is power in invisibility. It is the power of sight. I can see what others cannot.

How can a President build detention camps on U.S. soil, deploy the military to U.S. cities, threaten to annex foreign land, or bomb boats in the Caribbean without Congressional approval? Because the United States first gave its President this power, so it could take more Native land.

The rise of fascism in the United States is the natural outcome of a country that has never acknowledged its own history. The rise of fascism is that history coming home to roost.

This whole time, I thought what Americans couldn’t see was Indigenous people–our history, our truths, our contemporary lives. But then I realized that without us, they cannot see their own country.

I want to hear from you! Follow Rebecca on substack: https://open.substack.com/pub/gohini/p/erasure-is-how-anti-indigenous-racism?utm_campaign=post-expanded-share&utm_medium=web

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please: Share your reaction, your thoughts, and your opinions. Be passionate, be unapologetic. Offensive remarks will not be published. We are getting more and more spam. Comments will be monitored.

Use the comment form at the bottom of this website which is private and sent direct to Trace.