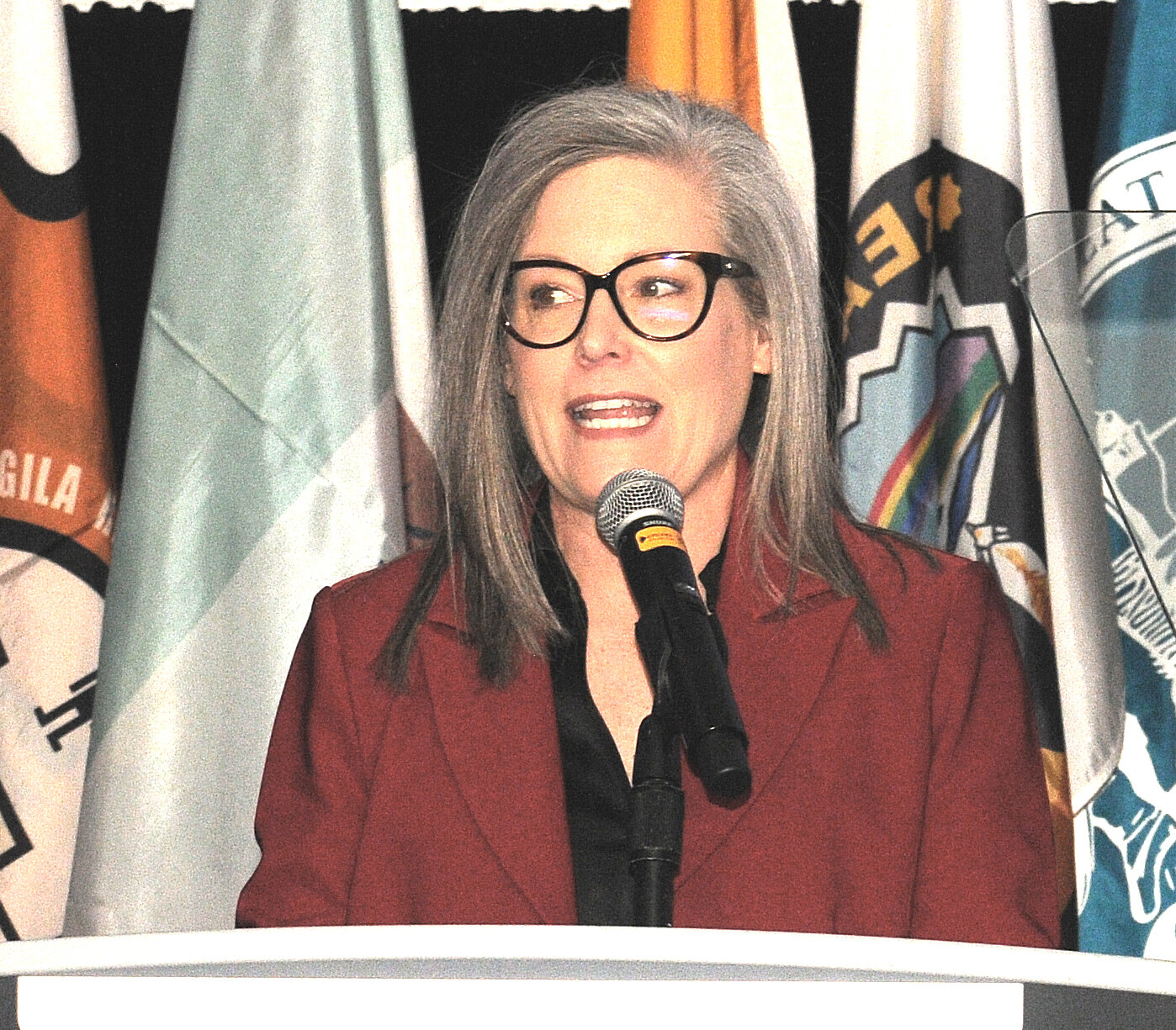

PHOENIX — Saying the process is too slow, Gov. Katie Hobbs said Wednesday she wants $7 million to speed up the repatriation of Native American human remains and artifacts.

In an address to tribal leaders Wednesday, Hobbs said the collection at the Arizona State Museum has continued to grow. The governor said that is hampered because there has been “no significant financial investment from the state.”

“It is time for that to change,” she said. “It is time for the state to take repatriation seriously.”

Stephen Roe Lewis, governor of the Gila River Indian Community, said he is glad the governor is asking lawmakers to help finance the effort.

But Lewis told Capitol Media Services the problem is not strictly financial.

“From what I’m hearing from certain tribal repatriation specialists, a lot of these institutions are not wanting to, or are dragging their feet to be in accordance with the federal law,” he said. Lewis said there needs to be a focus on those, though he said specifically said he will not call them “bad actors.”

“This shines a light on it,” he said.

Lewis stressed the money should help. But he said the focus by the governor will “make sure that this pushes these institutions along, that they’re under the microscope, at least in the state of Arizona.”

The governor’s request for more dollars drew support from Jim Watson, the acting director of the Arizona State Museum at the University of Arizona. He said it has about 4,000 human remains that have yet to be repatriated and “maybe 800,000 objects.”

“We’re an old, large museum and there’s a lot of material here,” Watson said, with some of the items going back to the 1920s.

He said money will help.

It starts, said Watson, with the fact that the building is 100 years old with limited space. And that, said Watson, has hampered the ability of staffers to do the necessary research.

It’s even more complex than that.

He said the federal Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act requires institutions that receive federal money have to facilitate the return of human remains and eligible other items. To do that, Watson said, they have to be brought out of storage, put them together in what he called “appropriate housing,” and either bring them to the affected tribe or have tribal officials come to the museum to take the remains.

He said a request for funding was made directly to the Arizona Board of Regents last year to at least fund some of the maintenance that has not been done over the years.

“They tabled it,” Watson said, with board members saying this is something that should be funded by the Legislature. And, so far, there has been no money forthcoming from the Capitol even though the facility was closed in August for anticipated maintenance.

“We’ve sort of been in limbo,” he said. Watson said the governor’s Wednesday announcement she will seek more funds came as a welcome surprise.

But even if there were more up-to-date space, he said that by itself won’t solve the problem.

“It takes awhile to pore through the archives and the objects and, in some cases, human remains to be able to identify all of repatriation-eligible items and individuals that we have,” Watson said. That, too, he said, is a function of not having enough money to hire more staff.

Still, Watson said the work has continued.

“We have been actively repatriating,” he said, saying the museum already has given about 50% of its collection back to tribes. And Watson said that began before the federal law was passed.

That still leaves the question posed by Lewis of whether there has been some “dragging of feet” by institutions that have built up collections of Native American artifacts.

“I would say that that thinking was probably when NAGPRA was first passed ... and people did intentionally drag their feet,” Watston said. “Within the past couple of years, I would argue there are a very few institutions that still have that approach.”

Still he said, there are those museums and others who need to be prodded.

“There’s evidence of that,” Watson said. He said new federal regulations were approved a year ago “that were specifically designed to force institutions to stop dragging their feet and remove some of the excuses they had often used to prevent repatriation from occurring.”

Some of those “excuses” offered he said included things like time, money and “the intricacies of doing the research.”

Then there is the question of “culturally unaffiliated remains.” He said some museums argued if they cannot identify to which tribe remains are related, they should just keep them.

Watson said the way the Arizona State Museum is working to deal with that issue is through an advisory board made up of representatives of all recognized Arizona tribes. He said they have found ways to reduce the number of these items to half of what was initially concluded.

What’s left, Watson said, are those remains for which there is no context to suggest to which tribe the remains belong other than “we think they came from Arizona.” What he suspects the advisory board will come up with is a plan to have tribal representatives or a single tribe to facilitate a single reburial “because we don’t have a good sense of where they’re coming from.”

It isn’t just the Arizona State Museum that deals with tribal remains and antiquities.

So does Arizona State University. And an investigation last year by Cronkite News and the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism at Arizona State University concluded last year that ASU had returned fewer than 2% of the remains it had to tribes.

Jay Thorne, an associate vice president at ASU, said the school takes issue with the report and disputes that 2% figure, though he did not immediately have a different figure. But he said that all this needs to be examined in context.

“It’s a complicated process,” he said, of categorizing and

repatriating returns. Thorne said the school works closely with tribes.

He said, though, the progress should not be measured strictly in the time involved.

“Everybody wants it done,” Thorne said. “But doing it fast isn’t necessarily the appropriate way of doing it.”

Hobbs’ request for the funds came as she gave a revised version of the State of the State speech she gave Monday to lawmakers. But aside from unveiling her $7 million ask, the Arizona governor added other comments specifically designed for the ears of the tribal leaders:

• Directing the Department of Public Safety to set up a version of the “Amber alert” program — designed to provide public notice of missing or kidnapped children — specifically for missing tribal members. She said more than 188,000 individuals went missing in 2023, including tribal members, who did not meet the criteria for the existing program.

• Asking lawmakers to expand the services provided by the state’s Medicaid program to include “traditional healing services so that indigenous people in this state can receive the health care they want.”

• Directing $4 million to four tribal colleges for scholarship and workforce programs.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please: Share your reaction, your thoughts, and your opinions. Be passionate, be unapologetic. Offensive remarks will not be published. We are getting more and more spam. Comments will be monitored.

Use the comment form at the bottom of this website which is private and sent direct to Trace.