"I felt so much pain that I had been carrying melt away."

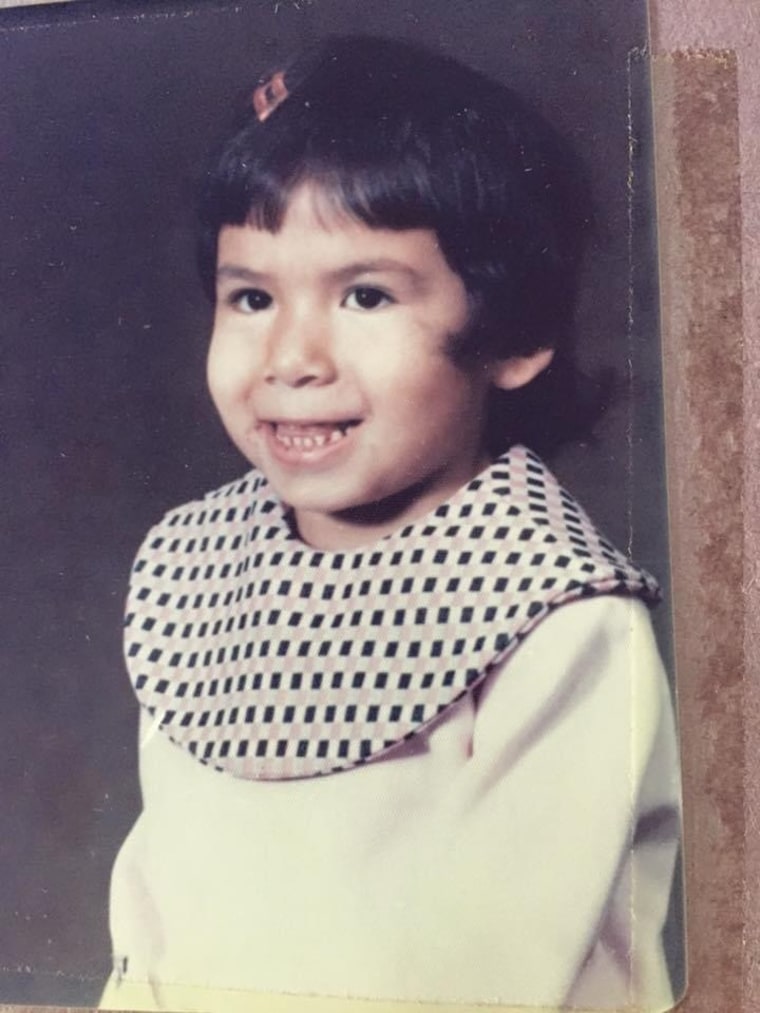

When I was a toddler, I was stolen from my home in the middle of the night. Child welfare authorities banged on the door and said, “We’re here for Yvette,” and my parents had no choice but to hand me over.

I’m one of more than 20,000 Indigenous children in Canada who were ripped from their families during what is known as the Sixties Scoop. The Canadian goverment believed that Indigenous people were not fit to raise children. In the words of former prime minister Hector Langevin, “To educate the children properly we must separate them from their families. Some people may say that is hard but if we want to civilize them we must do that."

Similar things happened in the United States, where an estimated 25% to 35% of Native American children were removed from their families before the Indian Child Welfare Act was established in 1978.

My siblings — I’m the youngest of 14 — were sent to federally operated, Catholic boarding schools where they were given English names and forbidden from speaking their aboriginal language. In these programs of forced assimilation, many experienced horrific physical, sexual and emotional abuse.

I was more fortunate.

In 1974, I was adopted by a white Christian couple in Oregon. They were told by the adoption agency that my biological parents didn’t want to raise me. For decades, I believed that story, too.

It was quite easy for a white couple to adopt an Indigenous child at the time. My adoptive parents started the paperwork in January, flew up in March to meet me for the first time, and the very next day they took me back to their home in Oregon.

Growing up, I was aware that I was Indigenous, but it’s not something that I embraced. At school, my classmates called me an Indian. Redskin was another one I heard a lot. My mom says I always asked her to buy me white tights so my legs would look white like the other girls. I didn’t want brown skin. I didn’t want to be different.

It wasn’t until my 20s that I started to get more curious about my history. My brother, who is half Japanese, had started looking for his biological family, so I decided I would, too. I knew my birth parents had the same name, Acoby, so I started by writing to every Acoby I could find in the Canadian providence of Manitoba.

The first person I heard back from was my sister Lorraine, who shared that we are members of Swan Lake First Nation. She said our parents had never stopped looking for me. When I read those words, I felt so much pain that I had been carrying melt away. I had spent my life believing that they didn't want me.

From Lorraine I learned about how our sister Charlotte was taken at a doctor's appointment when she was 5 months old. My mom handed Charlotte over to a nurse, not realizing she would never hold her baby again. My mom went back to that doctor's office every single day for months begging for them to let her see Charlotte, but she was gone.

At the age of 24, I reunited with my mother. My dad, a former chief of Swan Lake, had died a few years earlier. My sisters were there to translate for our mom who spoke only Ojibwe. She was relieved to learn I was raised by kind parents. For all those years she had wondered if I was OK, and I’m glad she was able to have some closure.

It’s so hard to put into words what it was like to be surrounded by people who look like me. There’s this feeling of acceptance. But at the same time, I feel so Caucasian when I’m around my biological family. Sometimes I feel like I don’t belong anywhere, which is not uncommon for survivors of the Sixties Scoop.

Since reconnecting with my birth family, I travel to Swan Lake reserve every summer. I feel at peace there. It’s just prairie land and it’s a part of me that I didn’t know I had been missing.

Now I have sisters that I text and call. We do big family dinners. When we’re together there is this overwhelming sense of calm.

I love sitting around with the council people and learning about where I came from. At my first powwow, I met family members I never knew existed — aunts, uncles, cousins. Unfortunately, the tribe can’t recognize me as a family member because the Canadian government erased my birth certificate. But I do have my Ojibwe name, which means Morning Sky in English. My kids now want to get their spiritual names.

I'm working to get my real birth certificate. The one I have now lists my adoptive parents as my parents.

I received a $25,000 apology check from the Canadian government. And that’s what my life is worth in their eyes. It’s like, "We destroyed your entire family. We took you from your home, from your family. Here’s a check for $25,000.” That hurts a lot.

There are so many people that don’t know anything about what happened to my people during the Sixties Scoop. One summer, I stopped at a burger stand just a few miles from Swan Lake and the woman working behind the counter had never heard of the Scoop.

I want the government to acknowledge what they did and honor those children who never made it out alive from their schools. Let’s call it what it is: The Sixties Scoop, like the Holocaust, was a genocide.

At least 4,120 children are known to have died in the residential schools in Canada. In the U.S., a federal investigation found that at least 973 children died in residential schools — and the actual number is probably much higher, since many were buried in unmarked graves.

My siblings were sent to those schools. They say their hair was cut off. They were beaten for speaking our language and singing our songs. They were forced to study the Bible. My sister Yvonne can only talk about it in little tiny segments because it was so traumatic.

We are healing together.

I will never forget how Swan Lake First Nation chief Jason Daniels welcomed me back.

"You're home," he said. "This will always be your home."

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please: Share your reaction, your thoughts, and your opinions. Be passionate, be unapologetic. Offensive remarks will not be published. We are getting more and more spam. Comments will be monitored.

Use the comment form at the bottom of this website which is private and sent direct to Trace.