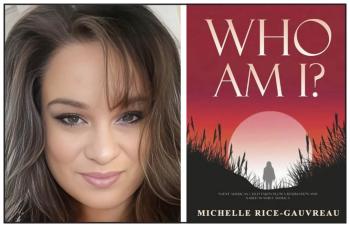

Memoir examines path from illegal adoption to finding herself as a “proud Mohawk woman”

Summary

Windspeaker.com

Like many adopted children, Michelle Rice-Gauvreau believed that meeting her birthmother and extended family would save her.

Instead, the first time she travelled by bus from Connecticut to Montreal and then by borrowed car to the Kahnawake reserve resulted in culture shock.

“It was tough at 15 (years of age). And I was so headstrong. I was like, ‘Oh, I have a family. Maybe they'll rescue me.’ Right. Every adoptee might have that fantasy. Little did I know the culture shock I was going to get because I was not raised on the reservation. I'm being raised in white society,” said Rice-Gauvreau, 54.

In Who Am I?, a self-published accounting of her life from birth, Rice-Gauvreau traces her time from the hospital room of her delivery and her illegal adoption by Tom Rice, also of the Kahnawake reserve, to growing up in Connecticut where Tom lived.

When Tom dies before Rice-Gauvreau turns three years old, she is raised by Lea, Tom’s widow. Lea suffers from mental illness, which in part presents through hoarding and controlling her adopted daughter. Rice-Gauvreau lives in a filthy, moulding, cluttered house until Lea sends her away, first to live with an aunt and finally into the foster care system.

Rice-Gauvreau dedicates her memoir to Tom.

“I don’t think I would have wanted for anything (had he lived). I was told I was a Daddy’s girl,” she said. “I think everything, all of my needs, would have been met. I don't think he would have let my adoptive mother hurt me the way she did.”

Then again, she admits, that could be another adopted child’s fantasy.

“I'm sure I romanticize it a lot, but I also go by the stories that I was told, too, about him,” said Rice-Gauvreau.

Her memoir is a hard-hitting journey through pain, numbness, anger, and depression to forgiveness and understanding.

Like many Indigenous children in the 1960s, Rice-Gauvreau was given up because of poverty. It’s not an aspect she examines in any depth in her memoir because, she says, “it was a common-sense type of thing” to understand.

And because of that, Rice-Gauvreau says, she never had to forgive birth mother Sharon Armstrong, who she understood had no choice.

Sharon was living with her mother Mary, who was already raising Sharon’s first child, and she could not afford to raise and feed a second child. Rice-Gauvreau’s birth father had taken off. While in hospital, Sharon’s roommate became aware of the situation and contacted Tom.

Rice-Gauvreau would not learn that she was adopted until Lea’s sister told her at the age of 15. Her birth and baptismal certificates had been forged which presented another issue when Rice-Gauvreau needed to get a U.S. passport in order to travel into Canada.

Rice-Gauvreau did a few successive trips to Kahnawake in her late teens, including spending time with Mary before her grandmother passed away. However, it wasn’t until she met up with foster parents Elaine and Geoff that she started to more fully embrace her First Nation heritage.

The British couple fostered only First Nations children. They co-founded the Connecticut River Powwow Society. It was at these events, Rice-Gauvreau writes, that her mind was “opened…to the spiritual world and the spiritual animals that are always guiding us.”

Rice-Gauvreau is continuing to learn about her Mohawk culture.

While today she is semi-estranged from Sharon and older brother Mike, she is in constant contact with one of her aunts. As for her birth father Eddie, he met her only once when she was a young adult and then cut off contact.

Rice-Gauvreau has no contact with Lea’s family. After Lea passed away, Rice-Gauvreau, with the support of her husband and son, spent five years sorting through Lea’s decrepit house. She sold many of Lea’s collectibles on eBay. The money from that she considers as her inheritance.

It was a hard job, she says, for her physical and emotional health to be in a house that held no good memories.

Rice-Gauvreau is continuing to learn that her feelings and experiences as an adopted child and adult aren’t unique for children or adults in her position.

For about one year now she has belonged to a group for adoptees, from which she gets support and gives support.

“I needed to feel what others were feeling. I needed to know that I was relatable to them,” said Rice-Gauvreau.

After writing her memoir, she says, she needed to connect with other people.

While putting her feelings and thoughts down on paper was cathartic, she says it was difficult.

“I still think about it. I still think about certain circumstances, absolutely. I think that happens with everybody. And I think it will always happen but I don't feel sorry for myself,” she said.

Writing her memoir came about in 2019 when she ended up in the hospital with sepsis and thought she might not make it out. She realized her only son Raymond, now 30, didn’t know her story. She started writing and even after learning she would recover, she kept on writing with the help of a book coach.

“I wanted to get my voice out there,” she said. “It took a long time. I also relived quite a bit. So I'm still kind of healing… but I think I'm doing a good job. That scab is pretty solid.”

And while that scab may be “pretty solid” now, in her memoir Rice-Gauvreau recounts the poignant goal of trying to make Sharon and Lea proud of her. Proud that after such a difficult beginning and upbringing, she survived and worked hard to get a college education. She now works as a legal professional in Connecticut.

Pride for her accomplishments is something Rice-Gauvreau feels only now for herself.

“If you asked me that five years ago, I wouldn't have said yes… because I don't think I knew where I was headed...I still didn't have a direction in my life, and that wasn't until I became sick. And then I realized, ‘Oh, I got direction. And I also have a voice and I need to use it.’.. I started writing and I started feeling my voice coming out. And that's where the pride started coming from,” she said.

It was frightening to put her life out there in a “very raw” way, she says, but her memoir, which came out in August, has received positive attention both in Connecticut and Canada.

At the end of her memoir, Who Am I?, Rice-Gauvreau answers the question, “So many events in my life shaped me into who I am today and that will never change. Growing up between two countries and two cultures, I now tell myself: ‘I am strong, I am thankful, I stand as a proud Mohawk woman. I am Michelle.’”

Who Am I? can be purchased at michellegauvreau.com

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please: Share your reaction, your thoughts, and your opinions. Be passionate, be unapologetic. Offensive remarks will not be published. We are getting more and more spam. Comments will be monitored.

Use the comment form at the bottom of this website which is private and sent direct to Trace.